That One Artifact: Snapshot to justice

Note: This series is based on real-world criminal investigations and some content may be graphic or disturbing.

Digital forensics is a demanding, high-pressure field, where the right combination of skill, training, and perseverance can be crucial to solving a case. The gravity of this work is immense, especially when a single digital artifact has the potential to break open an investigation. This responsibility is particularly heavy when the case involves a harmed child—or, as in this instance, one tragically killed. The significance of this work is undeniable, as the evidence uncovered can be pivotal in seeking justice for the victim and their loved ones.

This case study is part of my ongoing Magnet Forensics “That One Artifact” series. Previous articles have explored how various digital evidence artifacts have solved or significantly contributed to the investigation and prosecution of cases. In this case, a newly discovered artifact became the breakthrough evidence that led to the identification of a child’s killer and delivered justice to her and her family.

Responding to the call you never want to hear

While working an undercover assignment with my team in downtown Nashville, a call crackled over the radio from the opposite side of the city: “Units respond to a 10-70P (Burglary in Progress), 10-64PJ (Juvenile Deceased). Parents found their 12-year-old daughter unresponsive; fire (ambulance) is in route.” The police code translated into every officer’s nightmare—a residential break-in where a 12-year-old child was killed. It’s the type of call you never want to hear and one you can never forget.

In moments like this, every officer feels an overwhelming urgency, no matter their current assignment. You drop everything and rush to assist, even if your role is limited to securing the perimeter, taking witness statements, or providing whatever support you can. Our team specializes in digital forensics, and given the critical role digital evidence plays in modern investigations, we knew there was likely something we could do to help.

Assessing the forensics evidence on-scene

When we arrived, we signed in at the crime scene and got to work. However, after twelve hours of investigating, there was very little to go on. No witnesses, no surveillance footage, no physical evidence, and the only potential clue was the victim’s iPad mini, found in her bedroom where the crime had been committed.

But how significant could the iPad be, especially if the crime was committed by a stranger, as the investigation suggested? With no other leads and nothing else substantial to investigate after more than two days at the crime scene, we had no choice but to focus on the iPad, despite it being locked with an unknown passcode.

Challenges of the early days of mobile forensics

Before the development of Magnet Graykey, our department’s only option was to send the device to a digital forensics company and pay an exorbitant fee to have it unlocked and extracted. This period of digital forensics, which I refer to as the “San Bernardino/Snowden” era, was defined by Apple’s tightening of iOS security. As a result, our department had no way to unlock iOS devices in-house. We were left with the difficult task of prioritizing which cases were most urgent and then paying the steep fee for access.

After weeks of waiting, we finally received the full file system extraction of the iPad and I immediately got to work. I sifted through every file, app, and log, hoping to uncover even the smallest piece of evidence that might help solve the case. Every moment felt heavy, knowing that what we recovered—or didn’t recover—could make all the difference in such a heartbreaking and senseless crime. The pressure was immense, but the drive to bring justice to the child and her family kept me going. This, after all, is the heart of our work in digital forensics.

New iOS features lead to key evidence

One morning, after working late into the night on the case, I finally returned home around 2:00 AM. Exhausted, I sat down and unlocked my iPhone. As I swiped up, I stumbled upon something new—all my recently accessed apps appeared across the screen in a configuration that allowed me to swipe through them. One of these apps was Google Maps, and the map was showing me still at the office, even though I was clearly sitting on my couch at home. When I tapped the app, it instantly updated, showing my current location at home.

That moment immediately sparked a realization. My experience and forensic training told me that Apple was likely using an image to display recently opened applications. Today, we recognize this feature as App Switcher, and the artifacts left behind are known as “iOS snapshots.” At the time, however, this was a new feature, and forensic tools hadn’t yet caught up to identify the artifact. I likened this feature to recently accessed files and programs on a computer, potentially leaving behind a trace.

I headed back to the lab and immediately dove right in, focusing on the possibility that these snapshots might leave a trail of evidence. Although I didn’t expect them to be the breakthrough we so desperately needed, I knew they were worth pursuing.

A breakthrough from a snapshot

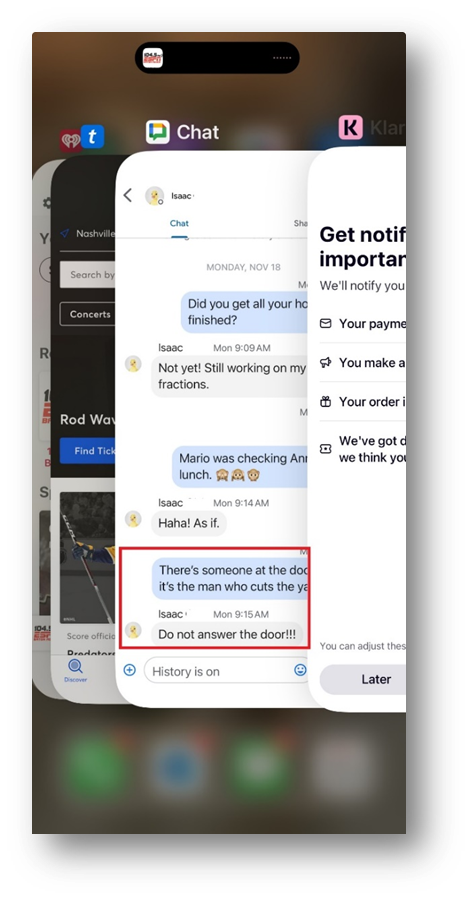

Suspecting these snapshots were simply images, I decided to revisit all the photos on the iPad, wondering if I had previously overlooked something. After filtering through the images by date and time, I confirmed these snapshots were photos. To my surprise, I discovered a snapshot that confirmed the victim had been chatting on Google Hangouts shortly before the time we believed the crime had occurred. Early in my analysis, I had manually examined the device for any messages in Google Hangouts, but there was nothing stored in the database and no hint the victim had used the app to communicate. The snapshot for Google Hangouts read:

Victim: “There’s someone at the door. I think it’s the man who cuts the yard.”

Other person: “Do not answer the door!!!”

Here’s an example of how Apple snapshots look today on an iPhone 15 Pro Max. Notice the Google Chat snapshot, which includes the recreated text I found on the victim’s phone.

Getting justice for the victim

During the initial investigation, homicide detectives had interviewed everyone who had access to the family, even the man who cut the grass at the family’s home. But there was insufficient evidence to suggest he was the suspect—until now. Additionally, DNA swabs were collected from various points in the child’s room, including the exit point from the bedroom window, and the DNA collected ultimately matched that of the gardener.

We also confirmed the identity of the party of the conversation and retrieved the same messages from their phone. Understandably, in the shock and grief following the child’s death, they had forgotten about the conversation.

As expected, this evidence proved to be powerful at trial. During closing arguments, the district attorney stated, “Detective Gish ensured the young girl’s voice was heard once more, helping to identify her killer.” A juror later confirmed the message from the snapshot was key in sealing the killer’s fate.

Crucial snapshots for other investigations

Since this case, I’ve discovered valuable evidence in iOS snapshots during other investigations, helping to reveal crucial details and solve complex cases. After all, sometimes it’s “That One Artifact” that brings a monstrous killer to justice and provides a grieving family with the closure they desperately need.

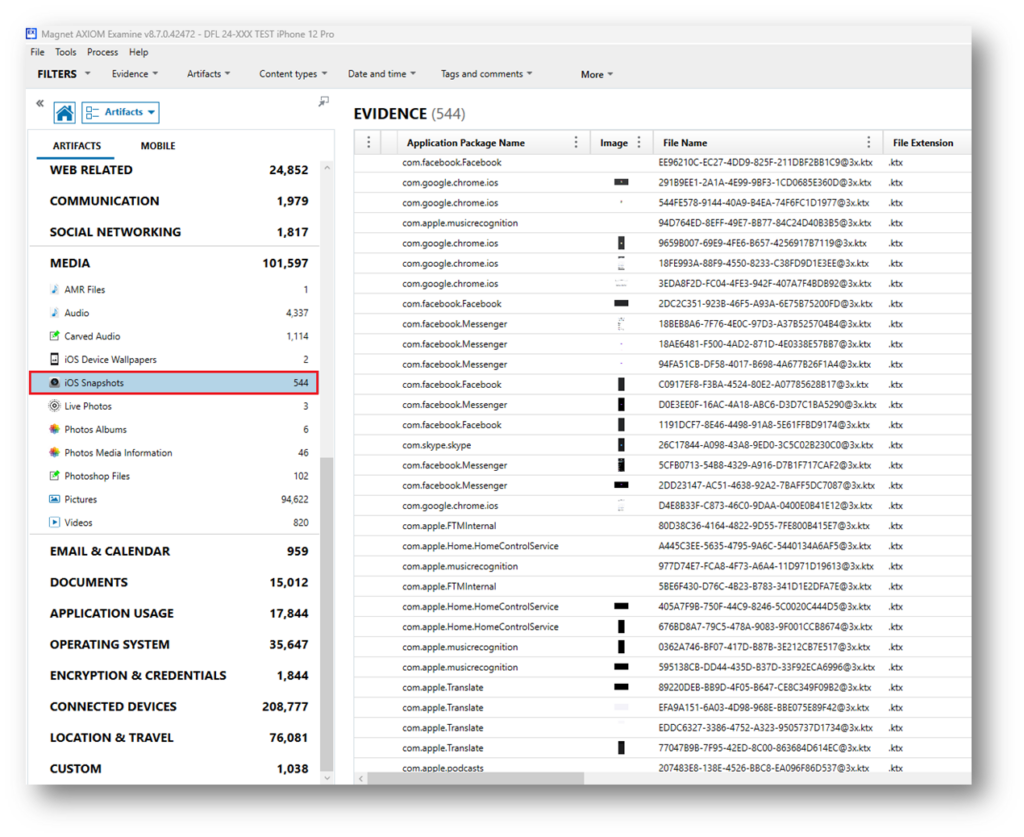

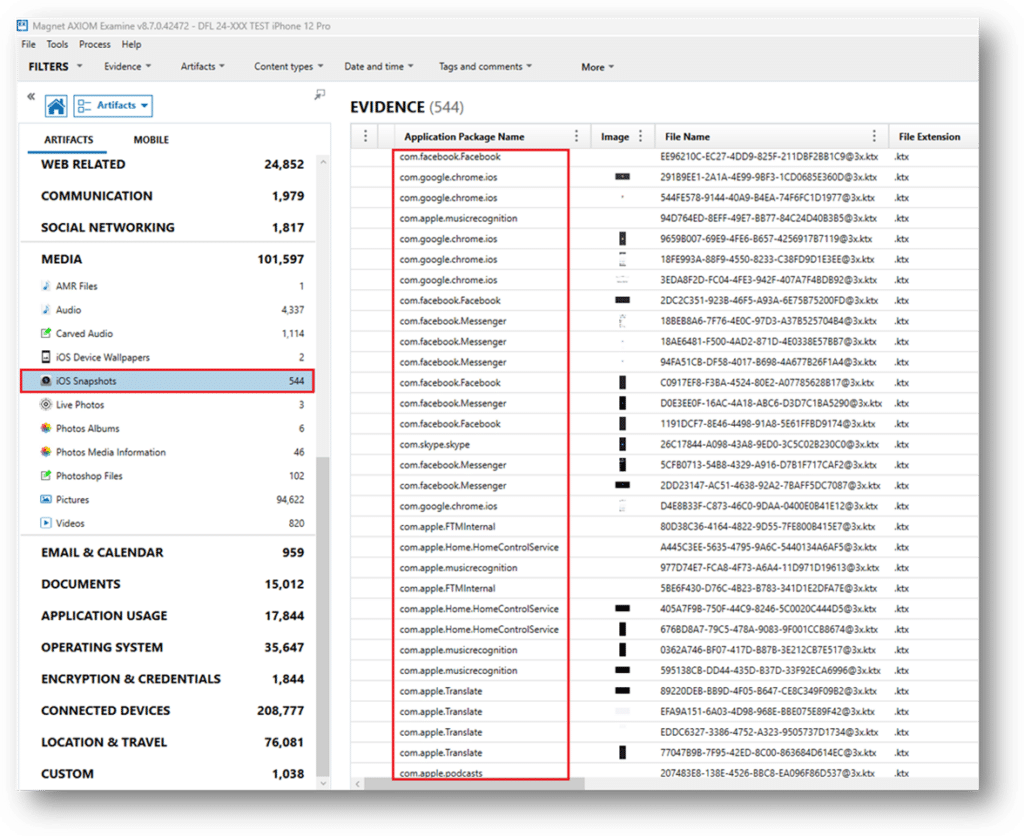

Apple’s App Switcher remains a powerful feature on iOS, and the artifacts it generates are even more prominent now than when I first worked on this case. Magnet Axiom excels at parsing these snapshot artifacts, organizing them into their own category under Media.

Axiom includes these snapshots in the Media category under iOS snapshots.

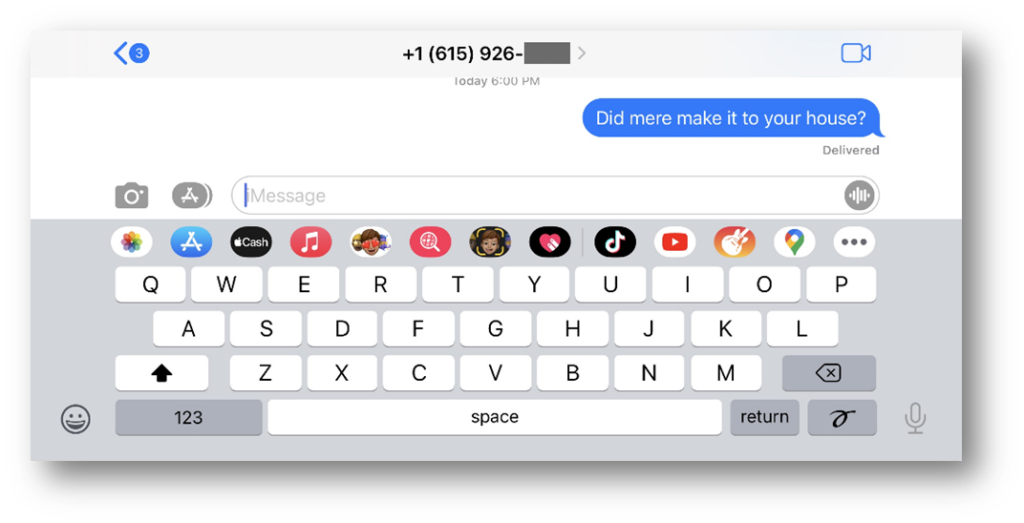

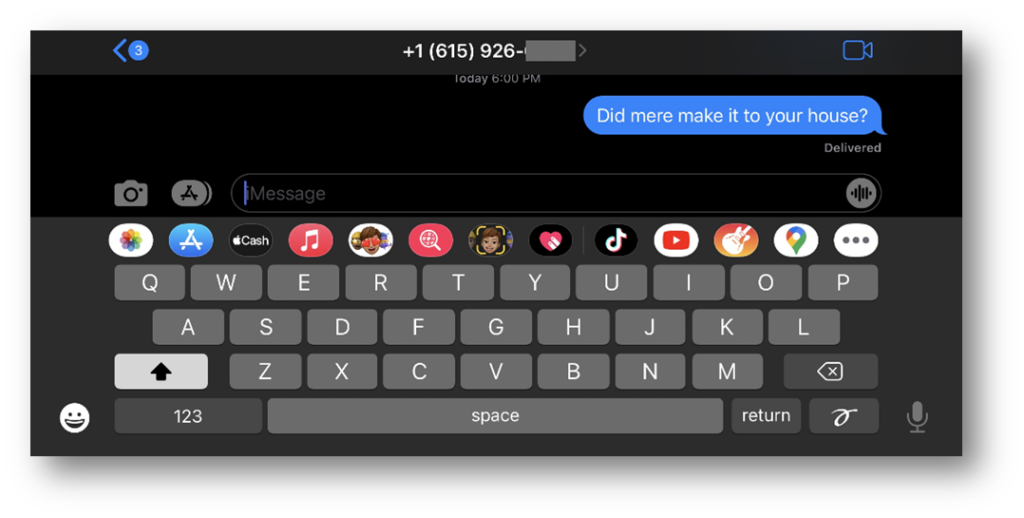

Apple now stores snapshots in the KTX (Khronos Texture) file format. Additionally, two versions of each snapshot are created—one for light mode and one for dark mode—ensuring the appearance remains consistent with the phone’s current display mode. This way, the iPhone’s style remains the same. Whether the phone is in light mode or dark mode, the snapshot will match the mode.

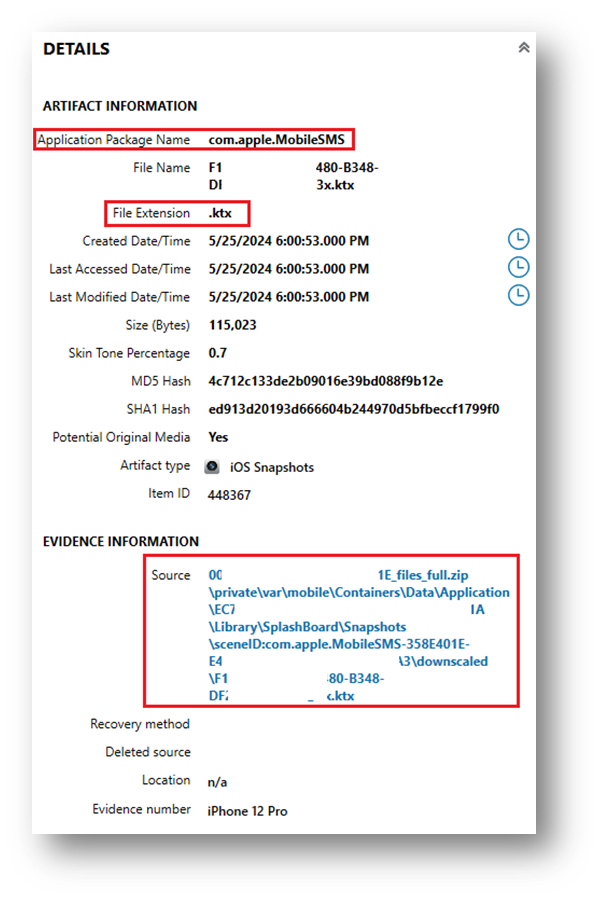

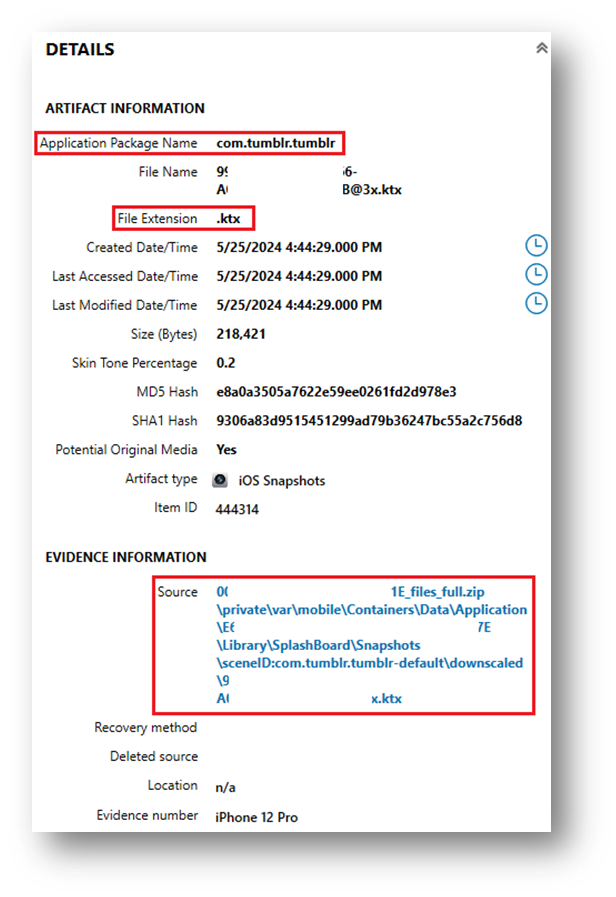

Here’s an example of an iOS snapshot from iMessages, featuring both the light and dark mode KTX files, as recovered with Axiom.

Modern KTX files are stored in the application bundle path from the app in which they were created.

Modern KTX files are stored in the application bundle path from the app in which they were created. In these two examples, the apps Tumblr and iMessages were used.

iOS snapshots can be recovered from a wide range of apps, often revealing the crucial, last-standing remnant of evidence that has been deleted. Imagine the potential evidence that could be uncovered—information that might identify the killer at the door. The following are only a few examples of KTX files from iOS snapshots:

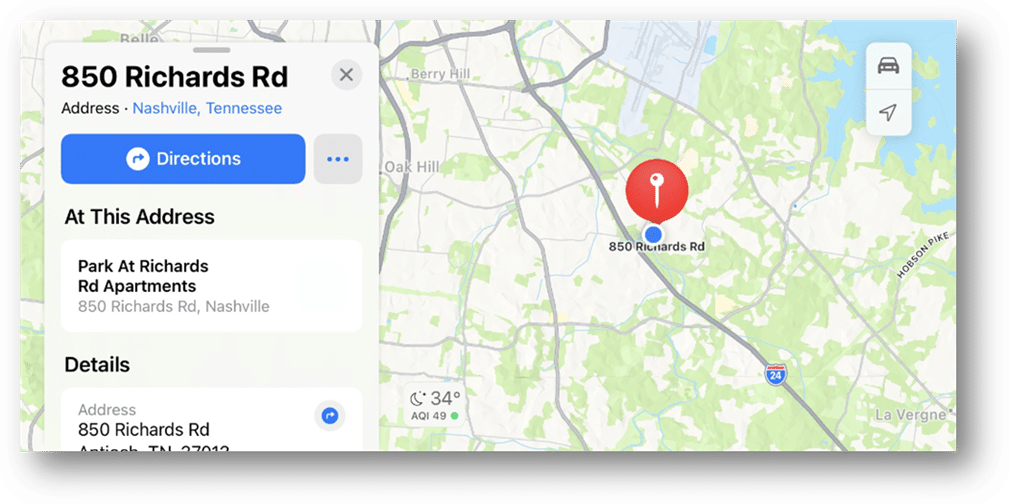

As recovered with Axiom: Mapping Programs.

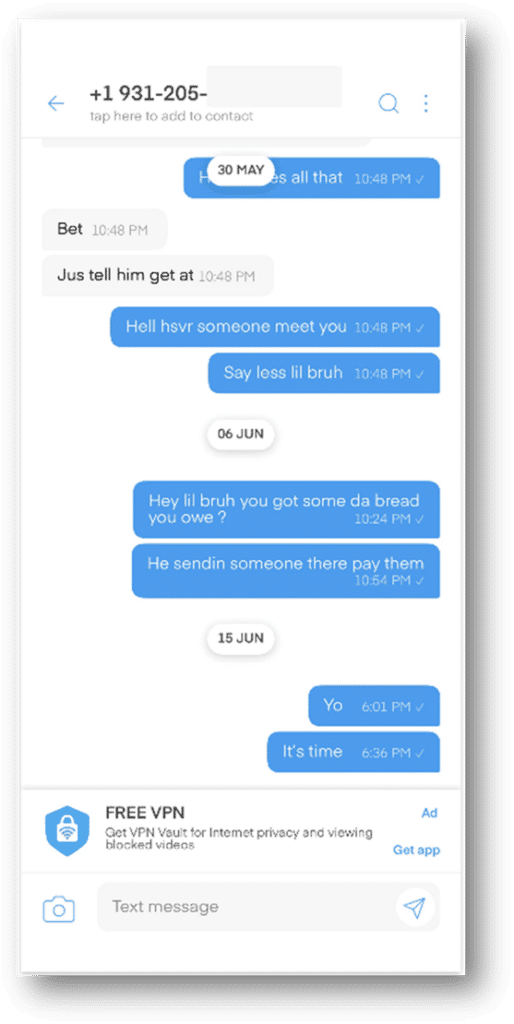

As recovered with Axiom: Messaging Apps.

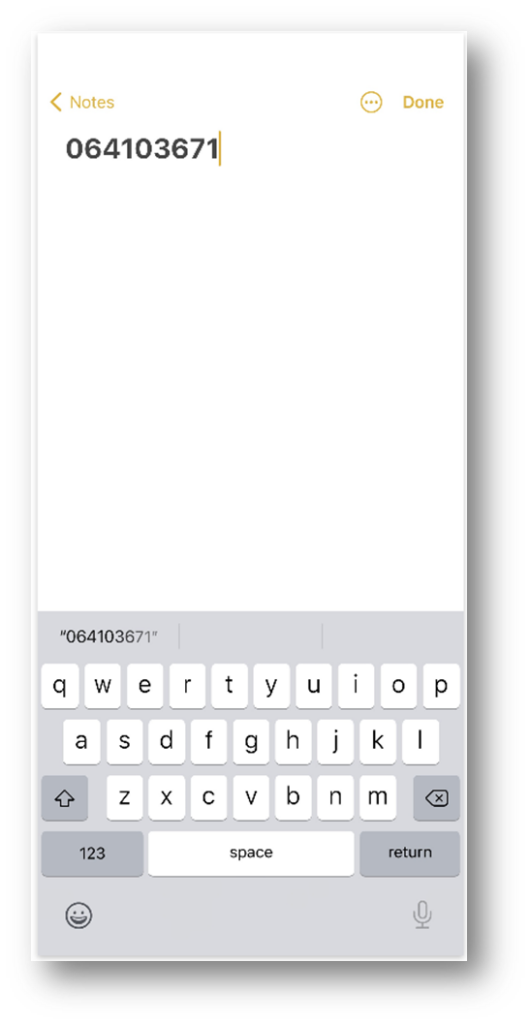

As recovered with Axiom: Apple Notes.

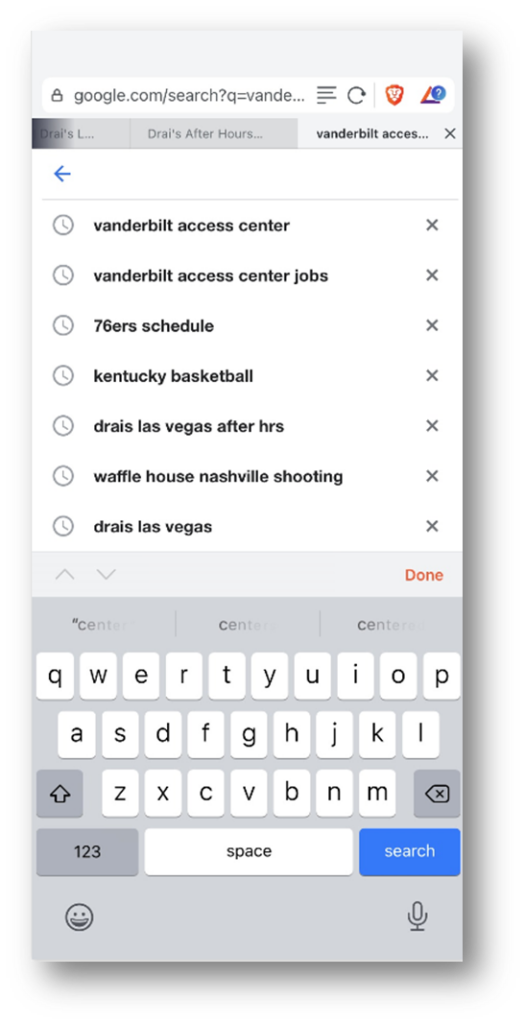

As Recovered with Axiom: Web Search.

To learn more about the importance of individual artifacts in different cases, read more of our That One Artifact series here. To explore Axiom’s broad artifact coverages for yourself, or request a free trial, contact sales@magnetforensics.com.